Understanding Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Symptoms and Treatments

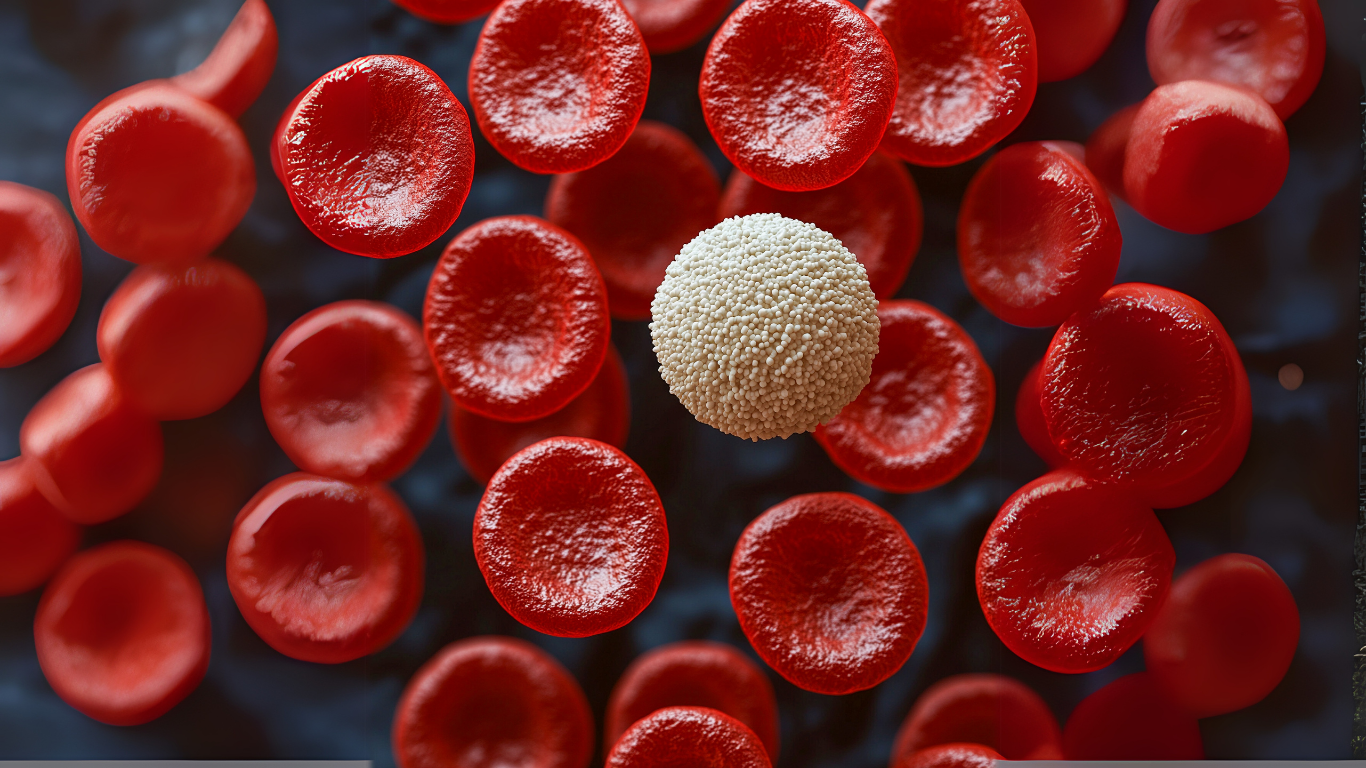

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is a fast-growing form of cancer that affects the blood and bone marrow. It primarily targets the lymphoid cell line, a crucial component of the body’s immune system, and results in the overproduction of immature white blood cells known as lymphoblasts.

These abnormal cells multiply rapidly, crowding out normal blood cells and impairing the body's ability to fight infections, transport oxygen, and stop bleeding. While ALL can occur at any age, it is most commonly diagnosed in children, particularly between the ages of 2 and 5. However, adults can also be affected, and their prognosis often differs significantly from pediatric cases.

Understanding the symptoms and treatment options for ALL is essential for early detection and effective management. Symptoms can vary depending on the stage of the disease but often include fatigue, frequent infections, unexplained bruising or bleeding, bone pain, and swollen lymph nodes.

What Is Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia?

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), sometimes called acute lymphocytic leukemia, is a rare blood cancer that affects the blood and bone marrow, where new blood cells are made. It causes the body to make large numbers of immature blood cells called leukemia cells, which don’t function like normal white blood cells.

These abnormal cells multiply quickly, leaving little room for healthy blood cells like red blood cells, platelets, and infection-fighting white blood cells. This disruption affects everything from oxygen delivery to the body’s ability to fight infection or stop bleeding.

Let’s explore how this disease works and who is most affected.

Types of Cells Involved: Understanding Lymphocytes

ALL specifically involves lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. There are two main types: B cells and T cells. Both play different roles in the immune system.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

-

B cells make antibodies to fight bacteria and viruses.

-

T cells help destroy infected or cancerous cells directly.

In ALL, the body starts producing too many immature B or T cells—but these cells don’t mature properly. Instead of fighting infection, they fill the bone marrow, bloodstream, and even other areas like the brain and spinal cord.

These leukemia cells can travel beyond the blood and bone marrow, reaching the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, or central nervous system. This is one reason ALL is so dangerous—it’s fast-moving and spreads quickly.

Acute vs. Chronic Leukemia: What’s the Difference?

When people hear the word "leukemia," they often don’t realize there are different forms of it, and the speed at which it grows makes a huge difference in treatment and outcomes. One of the most important distinctions in leukemia is whether it is acute or chronic.

So, what does “acute” actually mean in this context?

Acute Leukemia

In acute leukemia, the cancer develops quickly because the blood and bone marrow begin to produce large numbers of immature blood cells, especially lymphoblasts (in acute lymphoblastic leukemia). These cells don’t mature into fully functional white blood cells. Instead, they stay stuck in an early developmental stage and divide uncontrollably.

Because they are immature, they can’t perform the normal jobs of blood cells—like fighting infections or carrying oxygen. They also crowd out healthy cells in the bone marrow, leading to symptoms like extreme tiredness, infections, and easy bruising.

This type of leukemia usually becomes life-threatening within weeks or months if not treated. That’s why acute lymphoblastic leukemia and other acute leukemias are considered medical emergencies.

Treatment usually starts immediately and often begins with remission induction therapy using chemotherapy drugs to kill cancer cells quickly. Depending on the case, treatment may also involve stem cell transplant, intrathecal chemotherapy, or car t cell therapy, especially if the disease spreads to the brain and spinal cord.

Chronic Leukemia

Chronic leukemia, on the other hand, progresses slowly. The cancer cells in chronic leukemia are more mature and might still function to a certain extent, though abnormally. This means some people may not show symptoms for months or even years.

Doctors often discover chronic leukemia by accident—during routine blood tests. Since it progresses more slowly, the treatment strategy may involve careful monitoring at first, followed by medication or targeted therapy when needed.

People with chronic leukemia often don’t need urgent treatment right away, unlike those with acute lymphocytic leukemia. However, over time, chronic leukemia can transform into a more aggressive disease and require stronger treatments.

Causes and Risk Factors of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

When someone is diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, one of the first questions often asked is: “Why did this happen?” Unfortunately, there isn’t a single, clear answer.

Most people who develop lymphoblastic leukemia don’t have an obvious cause. But scientists have identified certain risk factors that can increase the chance of developing this type of blood and bone marrow cancer.

Genetic Predispositions

Some people are simply born with changes in their genes that may increase the risk of acute lymphocytic leukemia. These changes can affect how the body controls the growth of white blood cells. For example, children with Down syndrome are several times more likely to develop childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia than children without the condition. This isn't because of something their parents did or didn’t do—it’s because of how their chromosomes are arranged from birth.

There are other inherited conditions too, like Li-Fraumeni syndrome or Bloom syndrome, that can raise the chances. If someone in your close family had leukemia or other rare blood cancer, you might wonder—should I be tested for genetic risks? Doctors may suggest genetic counseling in such cases, especially if leukemia has occurred more than once in a family.

Environmental Exposures

Every day, we’re surrounded by things we don’t always think about—pollution, pesticides, cleaning products, even secondhand smoke. But long-term exposure to certain substances has been linked to increased leukemia risk.

For instance, people who have been exposed to high doses of radiation, such as survivors of atomic bomb explosions or those who received radiation therapy for another illness, have a higher chance of developing acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This doesn’t mean walking past a microwave or airport scanner is harmful—those use extremely low levels. But repeated or high-level exposure to radiation, especially during childhood, can be dangerous to blood-forming cells in the bone marrow.

Similarly, long-term exposure to chemicals like benzene in gasoline fumes or industrial settings may also damage blood cell DNA. A parent working in such an environment might ask—could this affect my child’s health? While the overall risk is low, long-term and intense exposure is something scientists continue to study.

Medical History and Previous Treatments

Some cancer survivors face an increased risk of developing acute lymphoblastic leukemia later in life, especially if they were treated with high doses of chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy. These treatments, while effective in killing earlier cancer cells, can sometimes damage healthy cells in the bone marrow, leading to future problems with normal blood cell production.

So, imagine a child treated for a brain tumor who later develops unexplained bruising and fatigue. A doctor might suspect acute lymphoblastic or acute lymphocytic leukemia, especially if the child had intensive treatment involving the central nervous system. That’s why long-term monitoring is important for all cancer survivors.

Inherited Syndromes

We touched on Down syndrome earlier, but it’s worth expanding. Children with Down syndrome are not only more likely to develop leukemia cells, but they also respond differently to cancer treatment. This can influence the type and intensity of therapies used, such as systemic chemotherapy or remission induction therapy.

Other inherited conditions like neurofibromatosis type 1 or ataxia-telangiectasia are also associated with increased leukemia risk. These conditions affect how DNA repairs itself, and when DNA repair goes wrong, immature blood cells may grow out of control.

Common Symptoms of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a fast-growing blood cancer that starts in the bone marrow, where new blood cells are made. When someone develops this condition, the bone marrow starts producing too many immature blood cells, especially abnormal white blood cells called leukemia cells.

These crowd out healthy blood cells and affect how the body works. Understanding the early warning signs and physical symptoms of acute lymphoblastic leukemia can help you know when to speak with a doctor.

Early Warning Signs: What You Might Notice First

One of the earliest signs of acute lymphoblastic leukemia is feeling tired all the time. Not just the usual end-of-the-day tired, but deep fatigue that doesn’t go away after rest. This happens because the bone marrow isn’t making enough red blood cells, which carry oxygen. Without enough oxygen, your muscles and brain don’t get the energy they need.

Another common early symptom is fever. These fevers often don’t have a clear cause like a cold or flu. They may come and go or stay for days. That’s because leukemia cells crowd out the normal immune cells, making it harder for the body to fight infection.

You might also notice bruises appearing easily, or small red or purple dots on the skin (called petechiae). These happen when there aren’t enough platelets, which help stop bleeding. A simple bump might leave a large bruise, or a small cut might bleed longer than expected.

Ask yourself:

-

Am I getting sick more often than usual?

-

Do I have bruises I can’t explain?

-

Is my child more tired or pale than usual?

These questions may seem small, but the answers can help catch childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia or acute lymphocytic leukemia early.

Physical Symptoms: What Happens as the Disease Progresses

As lymphoblastic leukemia grows, it starts affecting other parts of the body. Bone pain is a common symptom, especially in children. They might complain that their legs hurt or avoid walking, even if there’s no injury. This pain comes from pressure inside the bone marrow, where leukemia cells are multiplying.

Swollen lymph nodes—especially in the neck, armpits, or groin—can be another sign. These lumps may or may not be painful, and they happen because leukemia cells can gather in the lymphatic system.

The liver and spleen may also swell, causing discomfort or a full feeling in the belly. If leukemia cells reach the central nervous system, a person may have headaches, trouble seeing, or weakness in parts of the body. In some cases, cancer spreads to the brain and spinal cord, requiring treatments like intrathecal chemotherapy—medicine injected directly into the cerebrospinal fluid to kill cancer cells.

How Symptoms Vary by Age

In Children

Children with childhood leukemia often show signs in subtle ways. A child who once loved playing outside may now want to nap instead. They might have pale skin, feel weak, or start missing school due to repeated illnesses. Bone pain is more common in kids, and they may limp or cry during diaper changes due to pressure in the hip bones.

Sometimes, the first symptom is a nosebleed that won’t stop or gums that bleed while brushing teeth. Parents may think it’s just growing pains or a minor virus, but acute lymphoblastic leukemia moves fast. If your child’s symptoms don’t improve after a few days, it’s time to ask the doctor about blood tests.

In Adults

Adults may have different symptoms. Fatigue, fever, and weight loss are often more noticeable. Adults might also notice swelling in the neck or belly, and more frequent infections like sinus or urinary tract infections.

Since these symptoms can be confused with other conditions, acute lymphocytic leukemia in adults may go unnoticed at first. But unlike kids, adults with lymphoblastic leukemia may respond differently to treatment and sometimes need stem cell transplant if chemotherapy drugs don’t work well.

When to See a Doctor

Some people delay going to the doctor, thinking their symptoms are nothing serious. But if you notice:

-

Unexplained bruises or bleeding

-

Ongoing fever without a known cause

-

Tiredness that affects daily activities

-

Bone or joint pain without injury

-

Swollen lymph nodes or belly

it’s time to speak with a doctor. A simple blood test can show changes in white blood cell count, red blood cells, or platelets. If leukemia is suspected, further tests like bone marrow biopsy, bone marrow aspiration, or spinal tap may follow.

Diagnosis and Tests for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Diagnosing acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) involves more than just noticing symptoms. A doctor needs to confirm the presence of leukemia cells and understand how far the disease has spread.

.png)

This is done through a series of tests that check the blood and bone marrow, as well as other parts of the body like the brain and spinal cord.

Each test provides a different piece of information to build a complete picture. Let’s walk through the main tests used to confirm ALL and guide treatment decisions.

Blood Tests and Complete Blood Count (CBC)

The first step often begins with a complete blood count (CBC). This test checks the levels of:

-

White blood cells

-

Red blood cells

-

Platelets (cells that help stop bleeding)

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia, these numbers are often abnormal. The white blood cell count might be very high or very low. Red blood cells and platelets are usually low because the bone marrow isn’t making enough healthy cells.

If a doctor sees large numbers of immature blood cells (called blasts) in the blood, it raises a red flag. These blastsshouldn’t be in the bloodstream—they’re supposed to mature inside the bone marrow first. Their presence may mean the bone marrow is releasing leukemia cells instead of healthy ones.

Bone Marrow Biopsy and Bone Marrow Aspiration

To confirm the diagnosis, doctors need to examine what’s happening inside the bone marrow—the place where all blood cells are made.

There are two types of procedures:

-

Bone marrow aspiration: A liquid sample of bone marrow is removed using a thin needle.

-

Bone marrow biopsy: A small piece of solid bone marrow tissue is taken.

Both samples are usually taken from the back of the hip bone. These tests are done under local anesthesia (numbing the area), and sometimes sedation is used, especially in children.

The samples are looked at under a microscope to check for the number of leukemia cells, their type (B cell or T cell), and how much of the bone marrow they’ve filled.

If more than 25% of the cells in the bone marrow are lymphoblasts (immature white blood cells), it confirms acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Imaging Tests and Lumbar Puncture

Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap)

In some patients, especially in childhood leukemia, the disease may spread to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord). A lumbar puncture helps check for this.

This test involves inserting a small needle between the bones in the lower back to take a sample of cerebrospinal fluid(CSF). This fluid surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

The CSF sample is tested to see if leukemia cells are present. If they are, treatment might include intrathecal chemotherapy, where drugs are injected directly into the fluid to kill cancer cells in the central nervous system.

Imaging Tests

-

X-rays, CT scans, or MRI scans may be used to look for swelling in the chest or signs of cancer cells in organs like the liver, spleen, or brain.

-

These scans can also help detect enlarged lymph nodes or bleeding caused by low platelets.

Genetic and Molecular Testing

Not all ALL cases are the same. Some types of leukemia cells have genetic changes that affect how the disease behaves and how it responds to treatment. Genetic testing helps identify these changes.

Doctors may test for:

-

Philadelphia chromosome (a gene change seen in some patients with ALL)

-

Other mutations in B cells or T cells

-

Proteins on the surface of leukemia cells that respond to targeted therapy

These results help doctors choose the most effective cancer treatment. For example, if the Philadelphia chromosome is present, treatment might include a targeted therapy drug like imatinib along with chemotherapy drugs.

Molecular tests can also track minimal residual disease (MRD)—tiny amounts of leukemia that might still be in the body after remission induction therapy. Detecting MRD early can help adjust the treatment plan to avoid relapse.

Treatment Options for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

When someone is diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the goal of treatment is to destroy the leukemia cells in the blood and bone marrow and allow the body to start making healthy blood cells again. This type of blood cancer spreads quickly, so treatment usually needs to begin soon after diagnosis.

Doctors don’t use the same treatment plan for every patient. The choice depends on age, type of ALL (like B cells or T cells), how far the disease has spread, and other health conditions.

For example, childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia might be treated differently than ALL in young adults or older patients. Below is a breakdown of the most common treatment options, what each one involves, and what patients and families might expect

Overview of Treatment Goals

Treatment for lymphoblastic leukemia usually happens in stages:

-

Remission induction therapy – The first phase. The goal is to wipe out as many leukemia cells as possible.

-

Consolidation therapy – To prevent cancer cells from coming back, especially in the brain and spinal cord.

-

Maintenance therapy – Lower doses of chemotherapy drugs to keep the disease away long-term.

Each step has a specific purpose. And while the names may sound clinical, they represent the plan to help the bone marrow recover and return to normal blood cell production.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the main treatment for ALL. These are strong drugs that travel through the bloodstream and enter the bone marrow, where they kill cancer cells. Since leukemia cells are spread all over the body, chemo has to reach everywhere.

Some chemotherapy is taken by mouth, while other types are given through a vein. In childhood leukemia, many children also get intrathecal chemotherapy, which is injected into the cerebrospinal fluid to treat or prevent spread to the central nervous system.

You might hear terms like systemic chemotherapy (goes through the whole body) or high doses used during induction therapy. Chemo drugs can’t tell the difference between cancer cells and some healthy cells, which can cause side effects—but those usually go away after treatment.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is less common for ALL but may be used if leukemia spreads to the brain and spinal cord, or before a stem cell transplant. It uses high-energy beams (like X-rays) to destroy leukemia cells in specific areas.

In some situations, a patient might need radiation therapy if leukemia cells are found in the testicles, spinal fluid, or lymph nodes. This isn't usually the first treatment doctors choose, especially in children, because of the potential long-term effects on bone tissue, growth, and learning.

Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

Targeted therapy focuses on changes in leukemia cells—like gene mutations or special proteins. One common target is the Philadelphia chromosome, a genetic change found in some patients. Drugs like tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., imatinib) block this abnormal signal and help stop the growth of immature blood cells.

Immunotherapy helps the body’s immune cells find and destroy leukemia. One example is CAR T cell therapy. In this treatment, a patient’s own t cells are changed in a lab so they can recognize and attack specific cancer cells. These new cells, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, are then given back to the patient.

These therapies are often used when standard chemotherapy doesn’t work, or if the cancer comes back. They are also being tested in clinical trials for both childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and adult ALL.

Stem Cell Transplant (Bone Marrow Transplant)

In some cases, especially when ALL returns after initial treatment, doctors may recommend a stem cell transplant. This is also called a bone marrow transplant. The idea is to destroy the patient’s bone marrow (which contains the damaged blood forming cells) with high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy, then replace it with healthy stem cells from a donor.

This new bone marrow can start making new blood cells, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Finding a good donor match is important—usually a sibling or someone from a donor registry.

This treatment is intense. It comes with increased risk of infection and other complications. But it may offer a better chance for long-term recovery, especially if the leukemia didn’t respond well to earlier treatment.

Clinical Trials and New Treatments

Some patients may qualify for clinical trials, which test new cancer treatment approaches. These studies can offer access to newer drugs or combinations that aren’t yet available everywhere.

For example, new forms of targeted therapy are being tested for precursor B cell ALL. Other trials are looking at better ways to deliver systemic chemotherapy, or how to improve outcomes with maintenance therapy.

If you’re facing tough decisions after relapse or if leukemia cells began growing again, your doctor might suggest a clinical trial as a next step. You can check current options through the National Cancer Institute or hospital networks.

Managing Side Effects

All treatments for acute lymphoblastic leukemia come with side effects. Some show up quickly, others might appear later. It's important to manage them so patients can stay strong during treatment.

Common side effects include:

-

Fatigue

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Mouth sores

-

Hair loss

-

Infections from low white blood cell count

-

Bleeding due to low platelets

To manage these, doctors may prescribe anti-nausea drugs, growth factors to boost blood cell recovery, or antibiotics to fight infection. If the central nervous system is affected, spinal tap and intrathecal chemotherapy might be done more frequently.

In some cases, bone marrow aspiration or bone marrow biopsy may be repeated to check how well the treatment is working. If needed, the team may adjust the plan—change medications, reduce the dose, or add extra support.

Conclusion

At PHO, we provide complete, holistic care for children, adolescents, and young adults with blood-related disorders and blood cancer like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Our team of skilled doctors, nurses, and specialists understands the physical and emotional challenges young patients face.

From the first blood tests to remission induction therapy, through maintenance therapy and long-term follow-ups, we are here every step of the way.

We focus not just on treating the disease, but also on helping each child live a full and healthy life—during and after treatment. If your child is newly diagnosed or already in treatment, we offer personalized care, using the latest therapies, clinical trials, and support services to help them get back to doing what kids do best: growing, learning, and living.

FAQs

-

Is acute lymphoblastic leukemia curable? Yes, many children and young adults with ALL can be cured, especially if treatment begins early and the disease responds well to chemotherapy and other therapies.

-

How is ALL diagnosed? Doctors use blood tests, bone marrow aspiration, bone marrow biopsy, and sometimes a spinal tap to find out if leukemia cells are present and to decide the best treatment.

-

Will my child lose hair during treatment? Hair loss is a common side effect of chemotherapy drugs, but it usually grows back after treatment ends.

-

What is the role of stem cell transplant in ALL? A stem cell transplant may be needed if the leukemia doesn’t respond to initial treatments or comes back. It helps replace damaged bone marrow with healthy stem cells.

-

Are there long-term side effects from ALL treatment? Some treatments can affect growth, learning, or other organs, especially in young children. That’s why long-term follow-up care is important—to catch and manage any problems early.

Comments